The word character – as long time readers will remember – did not mean dramatis personae. The word comes from the Greek meaning an engraved mark. As in to draw a character on a piece of paper. Put some together and it becomes a word. The term also meant to mark on the body, or the soul. It was not until a few hundred years ago that the term became applicable to a person in a story. Hamlet was not a character – the meaning changed more recent than Shakespeare’s death.

Read MoreThe concept for the Ocean Stone record grew from various places – my interest in long atmospheric and soundscape pieces, and in my exploration of Buddhist practice.

Read MoreOver half of my clients in the last five years wanted to write their book in order to make the next step in their public speaking career. The finished manuscript was not the goal. Instead, it was the lantern they let fly to show that they were there.

Read MoreThis creation whether it is writing a book, composing an album, making a film, or something else… is human expression. Call it for what it is and don’t devalue your expression. Don’t accept it for adequate when you want more.

Read MoreHuman expression is the focus of creative work. The focus is not polishing the piece beyond recognition. There’s a professional approach to the work – yes, for sure – but that doesn’t lose the focus of the human touch.

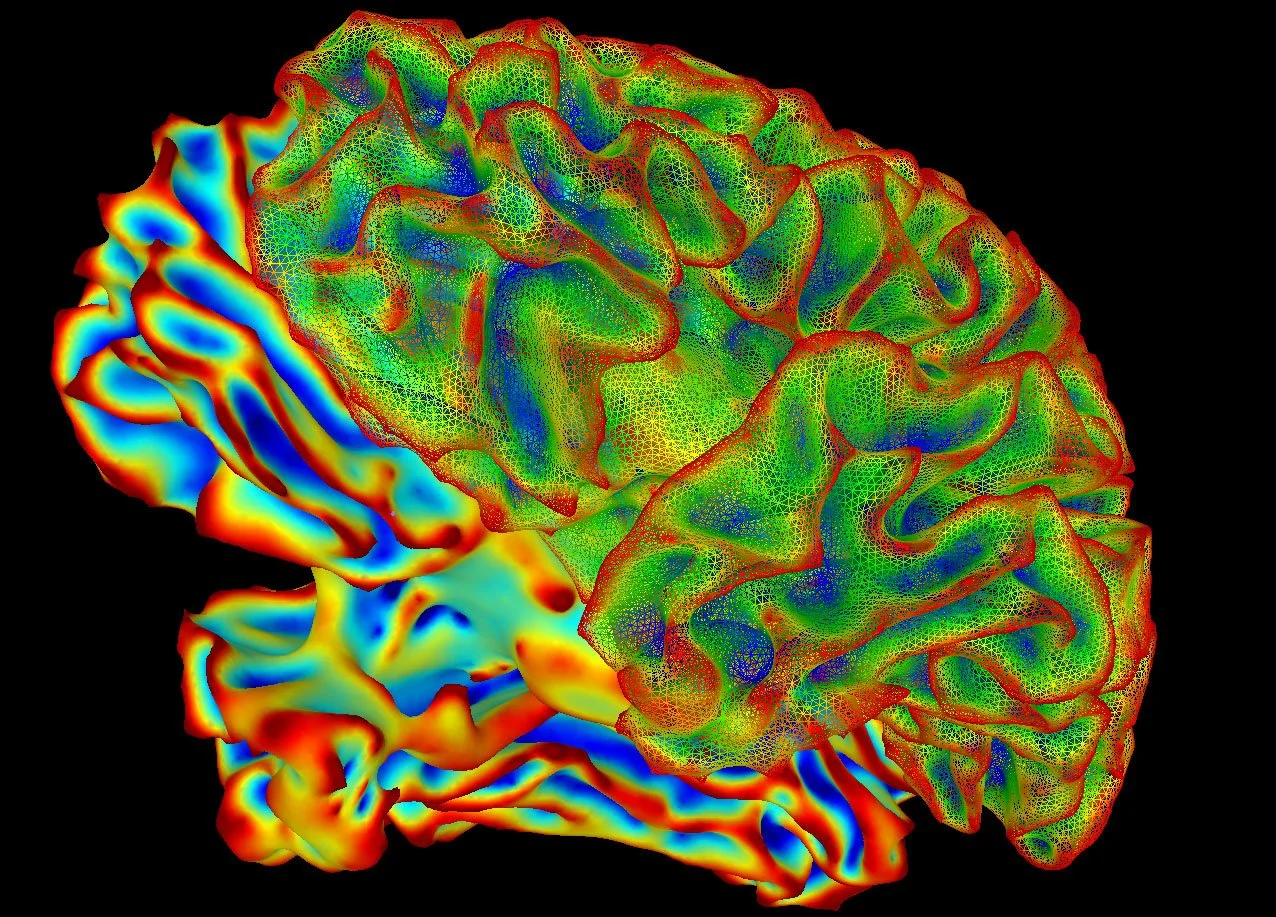

Read MoreIdeas develop. They grow. They need time and pollination from other parts of life. Other works of art. Other things you read and listen. A spark when they sit next to something unexpected. The brain makes the connection. It’s not fast. At times, it’s frustratingly slow. But it’s fascinating and it’s the process. It is worth it.

Read MoreThe book you start writing is not the one you will have when you finish. It always changes. Writing a book is a process. It’s human and it’s collaborative. It needs you to give into ideas and see where they lead. Explore what stands up strong next to something else. Be curious about what needs to shift to another part of the book. The idea changes shapes. The book evolves.

Read MoreAs a film student/aspiring screenwriter, Jean-Luc Godard’s films were hugely important to me. I’m hardly the first aspiring screenwriter or film student to have been inspired by his works. There are plenty of terrible student films trying to pull off the same magic.

Beyond his films, it was his creativity at finding solutions to problems that has stuck with me.

Read MoreI’ve been working on a novel through this year. It came to the point in writing this third draft where it was clear that one plot just wasn’t working. I cut it out.

Read MoreTaking the information in your mind and putting it on the written page is not an easy process. Even people who have a passion for writing – that’s most writers – battle with it. That shouldn’t hold you back from writing a book because there are other ways.

Read MoreWhen you read back through your manuscript – and you might even get a sense of these parts while writing – you will find passages or sequences that don’t hit the right note. The first step in this revision is ensuring the manuscript works overall. Only then can you tighten up the specific scenes.

Read MoreGhostwriting is an exercise in adaptation. My role is to adapt my client’s story or ideas to the written page. In some cases my clients have started with a wealth of material in their podcasts. The task, then, is to adapt hours of interviews and recordings to a book.

Here are three ways I’ve done that with recent clients.

Read MoreThere are times I work with an author who knows exactly what they want their book to be. In these cases it is usually a culmination of their work – many years of blogging and newsletters, years of public speaking or podcasts.

But there are times we discover the book on the way. Like an iceberg, there’s just part of it peering out of the water and we’ll discover the rest of it on the journey. Pull it into the light.

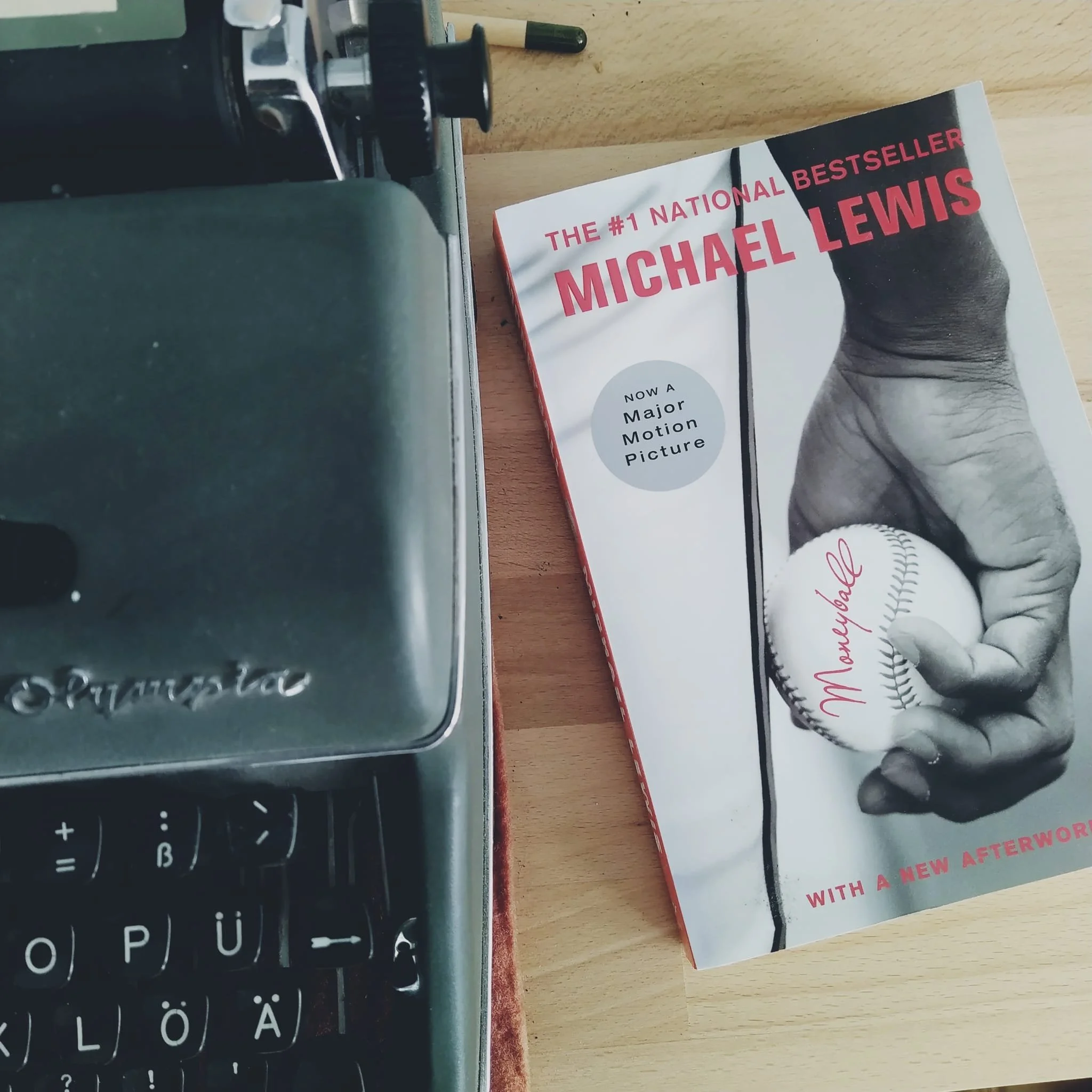

Read MoreTo cover a difficult topic in a way that’s as engaging as Moneyball, there must be a question that pulls us into the book. The chapters, or sequences, must develop from each other. Plunging head first into sabermetrics would have left most readers striking out part way through the first chapter. Instead, Lewis finds a way to open with the narrative to hook us, then deliver the ideas.

Read MoreRecently I was interviewed about ghostwriting and the question came up again: how do I feel about not getting credit for writing?

I’m fine with it.

Read MoreGhostwriting is an exercise in adaptation. My job is to adapt my client’s story or ideas to the written page in a way that captivates their readers. A handful of my clients started the process of writing their book with almost all their material on hand. They had their own podcasts.

Read MoreMoneyball – both the book and the film – is a great example of a story that grips your attention even though you know the end. If it was a straight sports story then the heartbreaking loss at the end of the season would be the climax. There would be different beats, a different focus, and more attention following the players. Instead, the climax of the story is not on the field.

Read MoreWriting a book is a huge undertaking. And when the writing is done, there is a massive relief.

The book is not finished.

I have seen friends and clients get too excited here and mess up the launch of their book. They had an amazing book, a real opportunity to make an impact, and then they rushed the end.

Read MoreSeveral writers I’ve consulted told me their idea for a story then sat back to watch my reaction.

My question was: what happens next?

There was a premise. They had a first act. It was the start of a story but it wasn’t a story itself.

Read MoreThe old writing adage says to “start as close to the end as possible.”

It’s also essential not to write a story thinking the end is the beginning.

At its heart, Story is about change. But it is not about triumph. It is about the journey there, the conditions that led to the change.

Read More