The word character – as long time readers will remember – did not mean dramatis personae. The word comes from the Greek meaning an engraved mark. As in to draw a character on a piece of paper. Put some together and it becomes a word. The term also meant to mark on the body, or the soul. It was not until a few hundred years ago that the term became applicable to a person in a story. Hamlet was not a character – the meaning changed more recent than Shakespeare’s death.

Read MoreThis creation whether it is writing a book, composing an album, making a film, or something else… is human expression. Call it for what it is and don’t devalue your expression. Don’t accept it for adequate when you want more.

Read MoreI’ve been working on a novel through this year. It came to the point in writing this third draft where it was clear that one plot just wasn’t working. I cut it out.

Read MoreTaking the information in your mind and putting it on the written page is not an easy process. Even people who have a passion for writing – that’s most writers – battle with it. That shouldn’t hold you back from writing a book because there are other ways.

Read MoreWhen you read back through your manuscript – and you might even get a sense of these parts while writing – you will find passages or sequences that don’t hit the right note. The first step in this revision is ensuring the manuscript works overall. Only then can you tighten up the specific scenes.

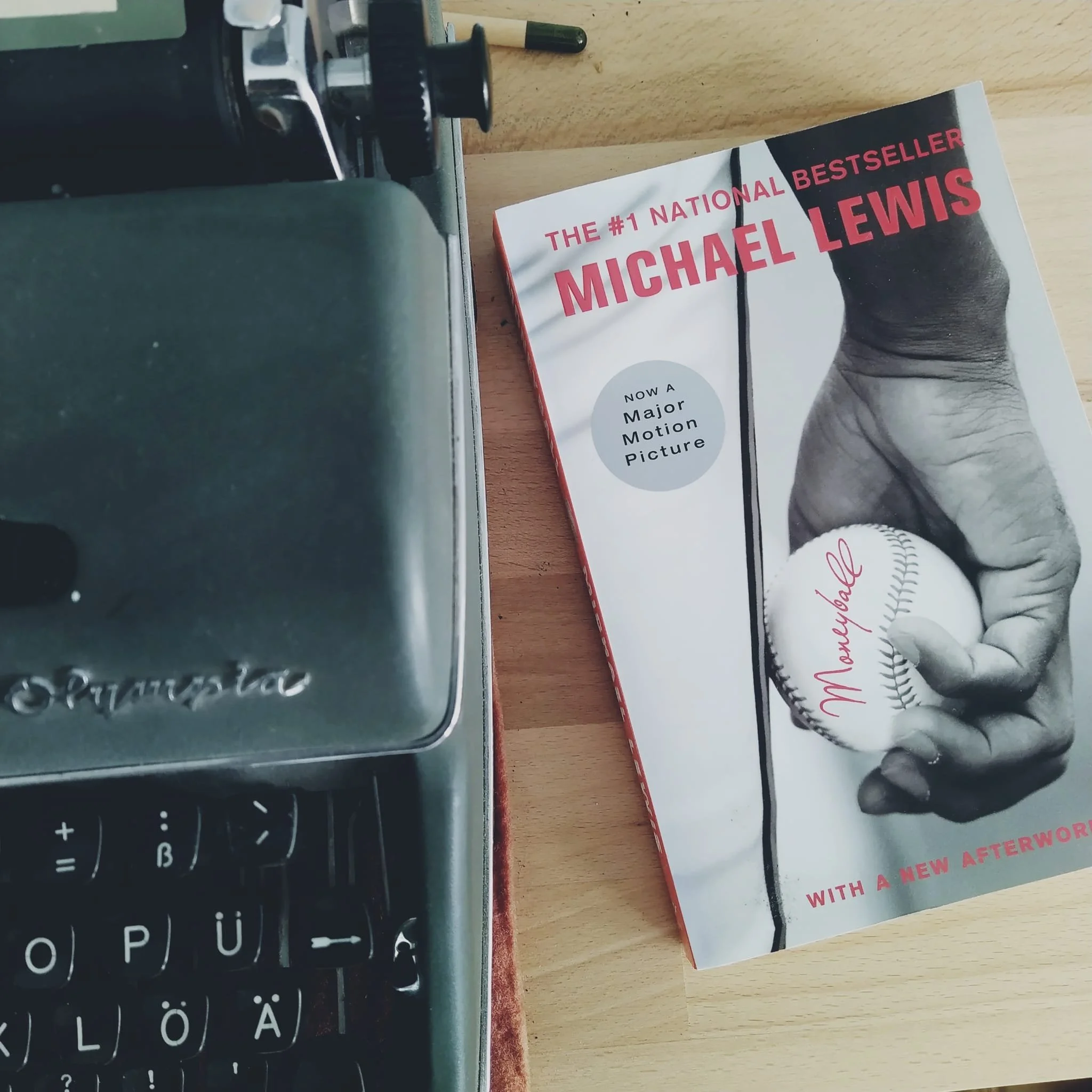

Read MoreTo cover a difficult topic in a way that’s as engaging as Moneyball, there must be a question that pulls us into the book. The chapters, or sequences, must develop from each other. Plunging head first into sabermetrics would have left most readers striking out part way through the first chapter. Instead, Lewis finds a way to open with the narrative to hook us, then deliver the ideas.

Read MoreMoneyball – both the book and the film – is a great example of a story that grips your attention even though you know the end. If it was a straight sports story then the heartbreaking loss at the end of the season would be the climax. There would be different beats, a different focus, and more attention following the players. Instead, the climax of the story is not on the field.

Read MoreStructure is essential to guiding your reader through your story. It’s giving information when it is needed. It’s shaping perspective on the events in the book. Structure is the scaffolding that holds up other elements of writing. It also gives you plenty of room to play. When you’re struggling with how things happen in the story, in the order they happen, take a look at what theme and value you are bringing to these events.

Read MoreRiddles require you to make up the context of the scene and find what fits. Stories build that piece by piece. There’s no cathartic emotional revelation in having the context given like this. There’s no story. There’s no value placed on this information. There’s no tension other than trying to solve the riddle. Stories require that the information we need – hopefully – comes right when we need it in order to make sense of what has happened.

Read MoreStories are about risk.

The world shifts. Something is changed – for good or bad. The character reacts to this to either try to make things go back to how they were, or to make things better.

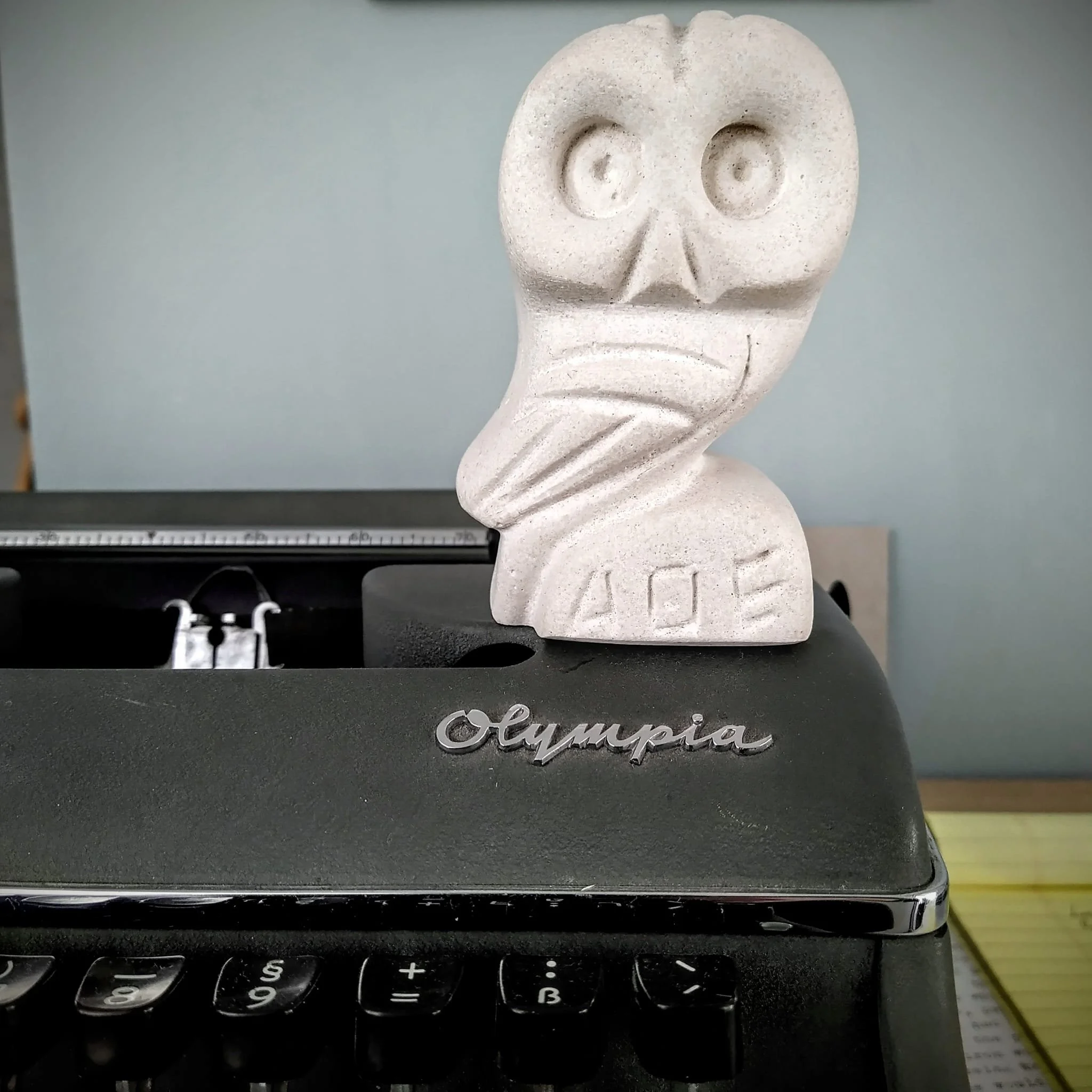

Read MoreAs in marking a character in stone. So, a face that shows character shows that which has been marked. Or deeply impressed.

The term didn’t come to mean a person in a story until the late 1660s – a good fifty years after Shakespeare had, as he put it, shuffled off this mortal coil.

Read MoreAll roads might lead to Rome, but you still have to find the road that works for you. There are many different ways to write and find your way through your story. But what works for someone else doesn't mean it's the way for you.

Read More